ISSUE 1 — Spring 2016

Appalachian ARts

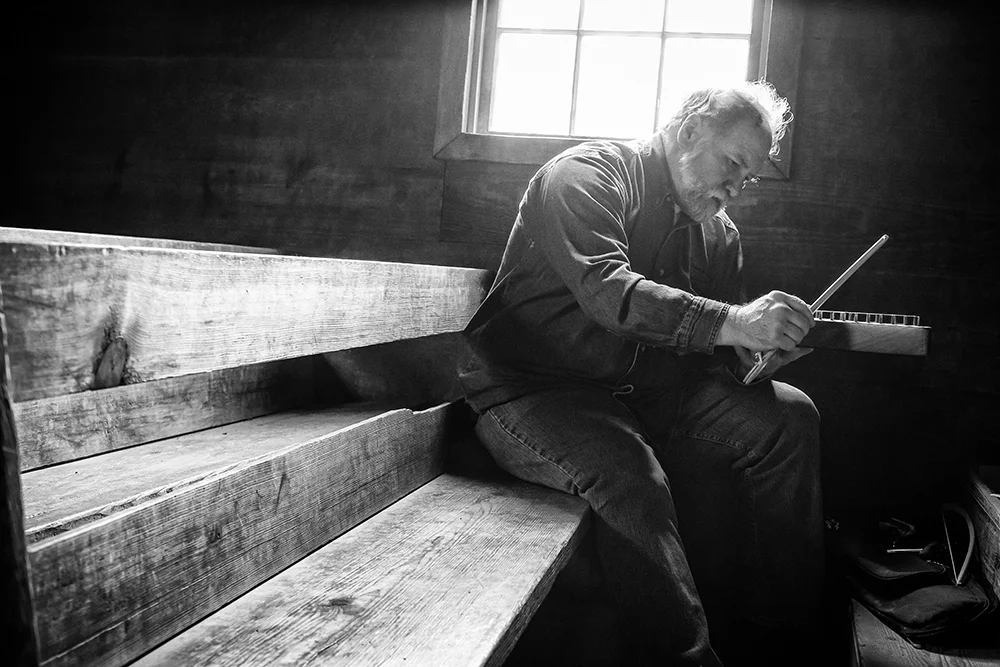

Sacred Space

AN Interview with Kopana Terry

Conducted by Vincent Trimboli, Appalachian Arts Editor

Kopana Terry works in many mediums: photography, music, drawing, writing, and on occasion, radio. As a musician she’s best known as the drummer for Arista Records’ Stealin Horses. Her writings are included in Arts Across Kentucky, D-Lib, and Kentucky Libraries among others. Along with exhibitions, her photographs have appeared in Spaces Magazine, Ilfopro, Ace Weekly, Louisville Music News, Lexington’s Herald-Leader and most recently in the documentary Kentucky Bourbon Tales: Distilling the Family Business. From 2006-2010, she was co-creator and senior producer for tonic: the arts and music magazine at NPR affiliate, WUKY. She’s been awarded grants from the Kentucky Arts Council, LexArts, and theKentucky Foundation for Women, and was commissioned a Kentucky Colonel in 1988. In 2003, her photo series Down the Backstretch: Women in the Thoroughbred Industry was awarded a citation of merit from Kentucky’s State House of Representatives. Her blog, the outhouse: where art goes, combines art with positive thought, and has a growing following. She earned her BA in Art Studio/Photography and Masters in Library and Information Science both from the University of Kentucky. Kopana was born and raised in Eastern Kentucky, in the Morgan County town of West Liberty. She currently resides in Lexington.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

The term Appalachian has so many personal connections for those that identify as such; For you, what does it mean to be an Appalachian Artist?

Being Appalachian informs virtually everything I do, sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically, but it's always there. I'm blessed to be from a very long line of Appalachians, and to have been raised in the Appalachian traditions. I can't imagine a life without that mountain spirit forming the core of my being. It provides an exceptional lens through which I view the world around me, and that is certainly passed on to my images. I'm quite proud of the meaning those Appalachian roots have given my life, and I trust it will always be a force in my work. I think at this point (age) there's little chance of it going away if it hasn't already....and it certainly hasn't!

Sacred Space seems to be an entwined theme in your work. Can you speak about some sacred spaces (perhaps the non-traditional) that inspire you?

When we hear the term Sacred Space, we're conditioned to think of a church, mosque, or synagogue; a building with four walls. I believe it's much wider than that, and it doesn't have to have walls at all.

Stories abound of African Animists giving thanks to the tree before they cut it down and turn it into a canoe. Pantheists revere nature. Native Americans believe water is our life giving force, and perform many rituals and prayers at the water's edge. Though I am myself a Christian, as an Appalachian I hold sacred the mountains I grew up in. In that way, the reverence for nature is not that foreign. And I, like many others of orthodoxy, often seek God in the outdoors. Who doesn't feel at peace during a long walk in the woods?At the same time, a sacred space can quite often be an individual, intimate place. It's not uncommon for Christians, Buddhists, Hindi, and perhaps Muslims (I'm not as familiar with their practices), to have personal altars in their homes where they might keep prayer candles, smudge sticks, icons/figurines, and other ephemera that act as conduit for prayer. There may also be places which aren't explicitly sacred to the greater world. It could be the old home place, a cemetery, or some other locale that holds a significant memory for an individual. For instance, the spot where a loved one died in a car crash: we see roadside crosses posted in tribute to the dead quite often these days. With time, any of these places can become sacred to large groups or a few individuals.

So, when I think of a sacred space, I try to think broadly, and not just about what I personally value as a sacred space. All the possibilities I've mentioned inspire me, and it's my exploration of these possibilities that advance my own spiritual growth. Each image becomes a prayer of sorts, because I must consider the greater nature of its meaning in the world, and ultimately, to myself. And it's the stepping outside of what I know, outside my comfort zone, that is as challenging as capturing a great image. It's learning what is sacred to others, and then finding a way to photograph it (them) in a way that is respectful. Many mainline Christian churches, for example, don't allow photos during service because the congregation is there in communion with God. It is an intimacy that should not be interrupted. I've been allowed to photograph a Native American water prayer but I had to do so without showing the communicant's face. This is why you don't see many people in the images at this stage in the series.

I liken the series much like circling a water drain: it has only just started along the edge of the whirlpool. The next phase is to go deeper, look closer at the spaces themselves as well as photographing those few people who are okay with sharing their time with the divine and my lens. It's not for everybody, and I totally understand that.

Do artists in other genres inform your images? If so, who and why?

If by other genres you mean other artistic media, the answer is yes. Without exception I'm most inspired by writers. In particular, I'm influenced by Appalachian writers like Gurney Norman, Silas House, and Mary Carroll-Hackett. In my readings, their words come from a place of spirit that speaks to me. I also enjoy those who write specifically on the topic of spirituality such as Anne LaMott, Nadia Bolz-Weber, and Thich Naht Hahn. Words have power. They provide perspective. They require contemplation. They reveal notions we may not have otherwise considered. Or perhaps they confirm what we knew, but were unable to verbalize, or make sense of.

If, on the other hand, you mean genres in photography, the answer is... maybe. I think at the end of the day I'm a documentarian, and others who work in this genre create images that I'm most often drawn to. Such photographers do indeed inform my own work.

My good friend Jahi Chikwendiu is at the top of the list. He does incredible documentary photography primarily with the Washington Post http://www.jahichikwendiu.com/.

I've long been inspired by Mary Ellen Mark http://www.maryellenmark.com/. I find her work to be a perfect marriage of the documentary and the artistic. It's a fine line really, and I'm always searching for it.

The WPA photographers still inspire me, particularly Walker Evans: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/1599/walker-evans-american-1903-1975/. And who wouldn't be moved by street photographer Vivian Meier?

But as far as photographers working in, say, landscape, architecture, abstract, fine art photography, I enjoy the work, but I wouldn't necessarily say the genres themselves inform what I'm doing with the exception of select technique. That's especially true when I'm shooting digital images (which I do out of necessity these days). I was trained in traditional film photography, and digital still feels so new to me that I often find myself lacking in technical prowess. Thank God I have photographer friends like Crystal Heis who are far more adept with technology than I am. They also happen to be generous in their advice. Color me lucky.

How does your work as an Archivist of Oral History inform the visual work you are creating?

Not much, really. If anything, it's the other way around. The more I photograph sacred spaces, the more interested I become in the people who created them. The images compel me to learn more about those spaces and those people. I find first person narrative intriguing. Memory and recall are complex. Ten people may experience the same event, but they recite their memories of that event in similar, yet differing, ways. It's a lot like a woven chair. The individual memory is a strand that, on its own, won't hold a single person. But when our strands are all told, they weave a seat that's sturdy enough to hold real weight. Our collective stories become more accurate together than apart. It's rather like a congregation of believers really.

At some point, I wouldn't be at all surprised if I include an oral history component to the series. Not only would this then include other voices - literally - in the conversation, but it provides another layer of exploration that, together with the images, could create something beautifully spectacular. It's all part of circling that drain.

Is there one space that you have always wanted to photograph?

I don't think I can pick just one. It would have been Stonehenge, but I have photographed it, though I would love to do so during the summer Solstice. That would be fantastic. Also, the Coptic Churches of Ethiopia I imagine to be exquisite as well. There are, of course, the many gorgeous cathedrals throughout Europe, particularly Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland. But I also rather enjoy churches that are no longer functional. Churches in disrepair are particularly interesting to me. So much love and energy went into building a place of worship, and then left to fall apart, is quite a story. For me there remains something sacred amidst the dilapidation. Spirit doesn't die.

I'm now in the second chapter of the Sacred Spaces series. New spaces, more people, more detail. I'm excited about circling the drain.